Archaeological Heritage vulnerable to Climate Change

door Annemieke van Roekel

Climate change poses a threat to archaeological heritage. However, archaeological heritage seldom appears in the IPCC-reports on climate change.

There is an urgent need to connect archaeology with this phenomenon, according to scientists, as rising sea levels and the increase of extreme weather events pose a real threat. Measures have to be taken to protect vulnerable sites, which often are situated in coastal areas. The general public can help, as various projects along Europe’s coast show.

Archaeological heritage sites provide us with information about past climates and adaptive strategies of Homo sapiens. Also in prehistoric times, settling in coastal areas had many advantages for early humans, such as the availability of marine food resources and transport possibilities. Coastal areas are therefore important in archaeological research.

But at the same time these sites are under a threat of climate change and other (semi) geological forces. Scientists analysed the IPCC-reports and came to the conclusion that both heritage and archaeology are seldom an issue related to climate change. Whereas storminess, floods and rising sea levels are increasing on a global and local level.

Main threats

Whether climate change is a natural process or induced by men, it is a reality. Main threats to our heritage, either cultural or scientific, are: flooding, desertification, sea level rise, erosion, drying of waterlogged deposits and acidification.

Experts say that there is a limited connection between the scientific world, heritage managers and the general public. So-called ‘public archaeology’ is a promising tool for supporting vulnerable sites. Public archaeology can be defined as engagement from non-professionals in (local) archaeology.

As heritage sites draw thousands of visitors, these places can also be an important resource for public engagement and education about climate change. Encouraging public awareness was already mentioned in the Rio Declaration in 1992, quoting: “Environmental issues are best handled with the participation of all concerned citizens” (UNEP, Principle 10).

Atlantic coast

An illustrative example of the involvement of the wider public in the protection of archaeological sites is the island Guidoiro Areoso in Galicia, in north-west Spain (top photo). Galicia has an extended coastline (1600 km), many archipelagos and extensive estuaries, such as Ría de Arousa. Situated max. 9 m above sea level with lose sediments of dynamic dunes, the island is typically sensitive to sea level rise.

As beaches on Guidoiro Areoso have been losing sand in the last two decades due to severe storms, more prehistoric sites have been uncovered. Some of them, located in the intertidal zone, have been lost shortly after their recovery. Local communities in this area have been involved in the protection of ‘their’ heritage in a crowdsourcing project. They were asked to send photographs, which were used by scientists for three-dimensional reconstructions of stone age monuments.

Passage tomb

Another example is a passage tomb on the Irish south coast of Cork, situated in the estuary of the river Ilen, near Baltimore. This passage tomb, of which several stones (orthostats and kerbstones) appear more clear at low tide, was discovered by a local couple, who contacted the University College Cork.

For scientists it is still an enigma why prehistoric people built their megalithic tombs in an estuary, as they must have known the site could easily flood. Geographers suggest it is possible that the vegetation was quite different during the Neolithic in this part of Ireland, providing some protection against flooding, or that intense cultivation upriver changed the channel system of the river.

Some archaeologists look for explanations in another direction: these tribes might have had a strong relation with water and therefore might have built their graves near the shore of rivers, lakes or seas. A vast water mass also provides a good view towards these stone age monuments, even from a far distance.

Coastal erosion at high speed

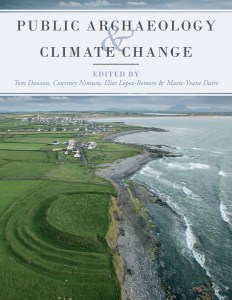

A special relation with water might also explain the short distance to the sea of the Neolithic monuments in the Orkney Islands, North-Scotland (see main photo). In the past the land surface of the Orkney’s was much bigger. The present archipelago of about 70 islands once consisted of only two land masses. [Hyperlink to: www.nemokennislink.nl/publicaties/steentijdmens-kon-goed-met-zeespiegelstijging-omgaan/ ]

The prehistoric village of Skara Brae – a World Heritage site – on the west coast of the main island, is an example of an archaeological site that has been uncovered by erosion of sand dunes during a severe storm in the 19th century, but is now also threatened by sea level rise.

In Scotland, public awareness of sea level rise and the consequences in the coastal regions is quite high. Scotland has 21.000 km (!) of coastline, of which 21% is soft (not rocky, such as pebbles and sand). The speed of coastal erosion nowadays has doubled compared to historic erosion.

Ten thousands of sites in Scotland are legally protected, but many more are not, of which a great percentage is situated in coastal areas. The unprotected sites are especially interesting for public engagement. The Scottish government plays an active role in the involvement of the general public.

Extension of citizen science

Public archaeology is an interesting extension of ‘citizen science’, a practice in which the wider public contributes to scientific projects. In the Netherlands, environmental organizations make use of an active audience, which helps to gather data about air pollution. The Dutch Leiden University developed an instrument to measure air pollution with a smartphone; thousands of citizens contributed to this iSPEX-project. The extensive and ever-growing possibilities of communication and data-gathering may facilitate projects in which the public can play a major role.

Further reading